I state without equivocation: Returning to graduate school to keep a job that I held for nearly 20 years was simultaneously the most difficult and intellectually satisfying time of my life.

Shortly after I began work in Montana State University’s Writing Center in 1993, I knew that I wanted a career teaching writing to college students. At the time, however, MSU had no graduate program in English. I could have driven over 200 miles to Missoula to earn a Master’s in English Literature, but based on my undergraduate work in English Education, I had come to believe that the study of imaginative literature had little to do with teaching writing. I, therefore, chose to enroll in Montana State’s Adult and Higher Education master’s degree program and focus on teaching and learning. The faculty in Montana State’s first-year writing program assured me I could easily gain employment teaching writing with that degree.

And they were correct. When I followed my then-husband to Michigan, I secured an adjunct position in both the first-year and developmental writing programs within hours of submitting my resume.

My training in teaching and learning–especially with the freedom I had been given to focus on teaching writing–meant that I was a pretty effective teacher, and I eventually used that effectiveness to earn full-time employment at the college.

My training in teaching and learning–especially with the freedom I had been given to focus on teaching writing–meant that I was a pretty effective teacher, and I eventually used that effectiveness to earn full-time employment at the college.

And just as my institution was facing its accreditation visit, the Higher Learning Commission (HLC) clarified its criteria for faculty preparation: Master’s Degree in the field being taught or a Master’s Degree plus 18 hours in the field. When it came to my fulfilling those 18 hours, I knew my administrators would enforce the letter and not the spirit of those guidelines. Since I had a particularly contentious relationship with the administrator who would make the final decision about my teaching credentials, I resigned myself to my fate. I investigated and found a rather affordable, all-online option in the Composition Studies program at Indiana University-East. I enrolled and paid the first tuition payment with help from the parents.

It was the fall of 2015. I was beginning my second year as interim director of our teaching and learning center. Less than two years after my divorce, I had nearly $10,000 of credit card debt and $25,000 home loan to pay for a new roof and siding. And, I was sick. After two years of physical misery, I was diagnosed with a variety of autoimmune issues (just as my employer-provided insurance rates skyrocketed).

I found myself in a situation few people would envy: I was in debt up to my eyeballs, had a limited support system, and desperately needed the health insurance my job provided. And without warning, I needed to spend a minimum of $10,000 to keep my job and hand over my precious free time to graduate studies.

I found myself in a situation few people would envy: I was in debt up to my eyeballs, had a limited support system, and desperately needed the health insurance my job provided. And without warning, I needed to spend a minimum of $10,000 to keep my job and hand over my precious free time to graduate studies.

By necessity, my world grew small over the next two years. I couldn’t afford much of a social life–both time and money were in short supply. I had to say no to many things, and some people whom I truly love (including my immediate family) became a smaller part of my life.

I started making more and more meals at home. To afford lunch, I cooked huge pots of soup and made them last all week. For the weeks I needed to spend my time grading essays, I invested in whatever frozen meals Meijer had on sale.

I woke up at 5 a.m. and read my course texts until my aching, arthritic joints actually felt like getting out of bed. I went to work, cared for my pets, did homework. I did the minimum amount of housework to get by. To me, it was all about survival.

And underlying all of this was the anger that I had to return to school when nearly 20 years of assessment data could demonstrate that I could already effectively teach writing to college students.

And underlying all of this was the anger that I had to return to school when nearly 20 years of assessment data could demonstrate that I could already effectively teach writing to college students.

The first course I took, “Stylistics,” was actually a fairly positive experience. Having never studied the subject in depth, I was learning new things, and I actually enjoyed my final 30-page paper, “The Grammar of Facebook.” On the non-academic front, however, things were getting worse rather than better.

I began to feel draggy, as if gravity had doubled. Blood work indicated that the medication I took for rheumatoid arthritis had begun harming my liver and had to be stopped. The increasing pain solely in my right foot meant that an old injury had never healed correctly; surgery was scheduled. Adding insult to injury, increasing health insurance premiums meant I was essentially taking a pay cut.

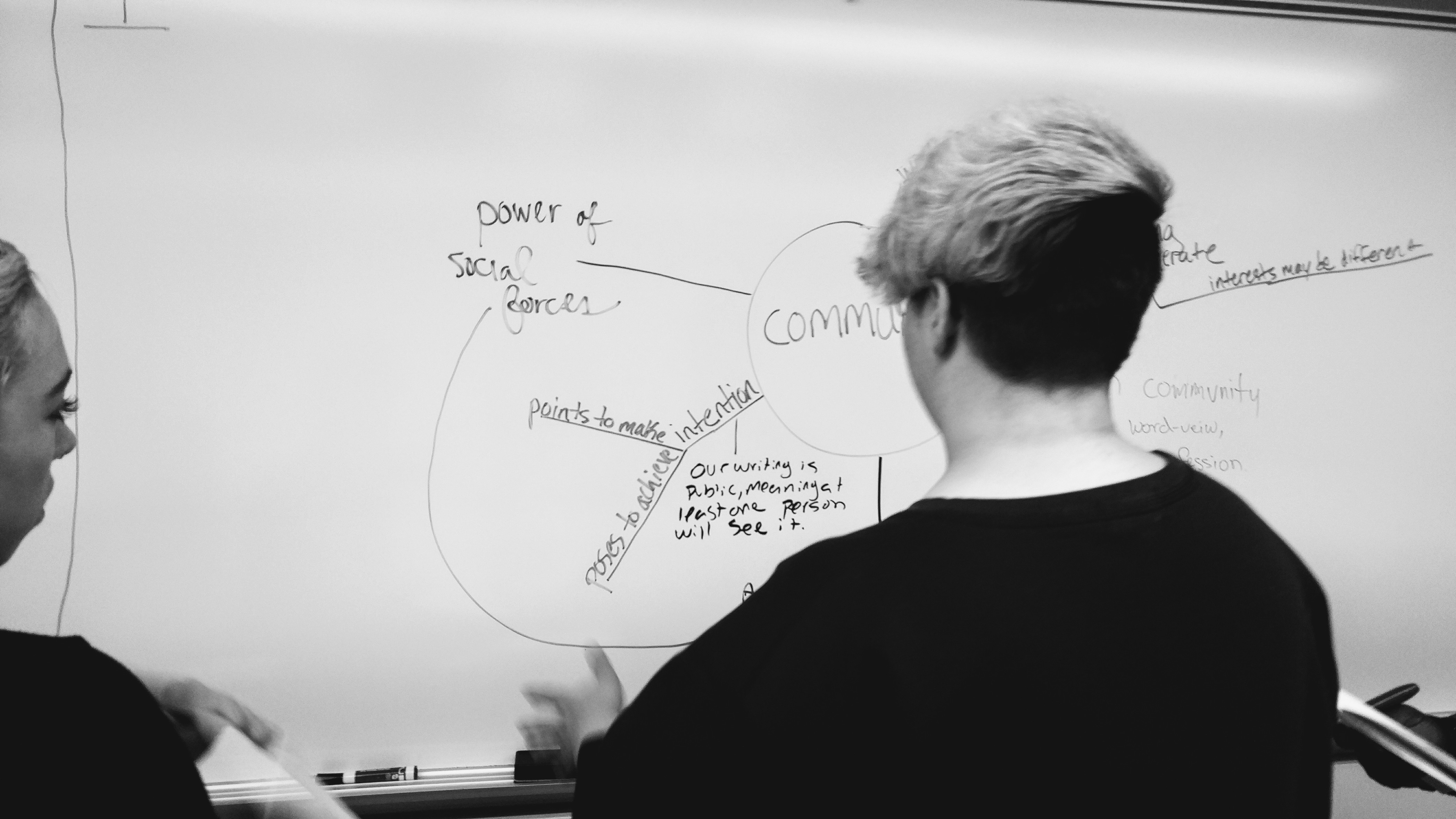

In the midst of this, I began my second graduate course, “Advanced Argumentative Writing.” Ironically, I led my institution’s argumentative writing course, Composition II, for eight years. Looking over the list of required/optional texts showed that I had read all but one. None of this improved my attitude, yet one new text increased my commitment ten fold to the type of argumentation I was teaching my students. Especially during the Trump-Clinton election season, I felt the overwhelming need to model reasoned public discourse for my students and demand it of them. I even named my newly created site for my Composition II public writing assignment “Civil Discourse.”

However, out of money and unable to drive myself anywhere for eight weeks due to surgery, I filed an appeal with my administration, arguing that my preparation and experience was already sufficient to teaching first-year writing.

I provided copies of the projects and papers I had completed on first-year writing pedagogy in my graduate education courses. I provided documentation about my internship, working with a developmental reading course that was attached to MSU’s first-year writing course–a model similar to the one my institution was developing at the time. I submitted evidence of how more than 90% of my students had successfully passed our composition courses–as judged by my peers, not by myself–when the course average was only in the 70-80% range. I provided evidence of my publications and presentations about teaching college writing.

I, of course, lost the appeal, but it bought me time to save for tuition. Still, money and time were both in short supply. Always looming over this was my health. After three years of feeling like death warmed over, I learned that taking care of myself was more important than any modern drug the rheumatologist could prescribe. Eating right, getting eight hours of sleep, exercising regularly, and avoiding stress were of utmost importance.

I, of course, lost the appeal, but it bought me time to save for tuition. Still, money and time were both in short supply. Always looming over this was my health. After three years of feeling like death warmed over, I learned that taking care of myself was more important than any modern drug the rheumatologist could prescribe. Eating right, getting eight hours of sleep, exercising regularly, and avoiding stress were of utmost importance.

But, I certainly wasn’t going to avoid stress. I was now in my third year as interim director of our teaching and learning center; we were understaffed, and the provost would not allow me to hire anyone. I was in graduate school so that I could keep my job and therefore my insurance. Consequently, time wasn’t going to always allow for eating right, sleeping enough, or exercising regularly. So, I circled the wagons, made my life even smaller. My life became largely work and school (which was really just an extension of work). Again, as a matter of survival, the friends and family whom I could regularly give time withered to a tiny group. I can actually count them on two hands. By necessity, some people whom I love, including my own brother, became less important parts of my life. I only had so much to give emotionally and physically.

In January 2017, I returned to my graduate work with a course called “Contemporary Literacies.” All of the reading and thinking I had done prior to re-entering grad school had led me to believe that we should be teaching for “rhetorical flexibility,” that somehow I need to be teaching students more than just how to write a college essay, that I should be giving them the ability to write in any situation they encounter. Everything about the Contemporary Literacies course confirmed what I had already come to believe–only instead of basing my conclusions on personal experience and the occasional scholarly reading, I was studying the best of current and past scholarship that confirmed my beliefs.

Yet, instead of getting angry that I was again learning something that I already knew, I became a radical. I could no longer return to the way I had been teaching composition, and I felt I could no longer tolerate my institution’s tolerance of instructors teaching writing by assigning four, five-paragraph, apples-oranges-pears essays. I may have been shipped off to grad school as the “least prepared” full-time English faculty member, but I would return ready to start a revolution.

Yet, instead of getting angry that I was again learning something that I already knew, I became a radical. I could no longer return to the way I had been teaching composition, and I felt I could no longer tolerate my institution’s tolerance of instructors teaching writing by assigning four, five-paragraph, apples-oranges-pears essays. I may have been shipped off to grad school as the “least prepared” full-time English faculty member, but I would return ready to start a revolution.

It would just all have to happen when I was finished with my classes. And I still had two more to take: Teaching Composition I and II. My closest friends and colleagues laughed or groaned when I would describe the last two classes. Indeed, the basic techniques for teaching composition were not new to me. However, I was reading scholarship I read 20 years previously in a new light and I was reading current scholarship that not only reinforced my views but radicalized me further.

Ironically enough, those last two classes happened against a backdrop of turmoil at work. I began my fourth year as interim director of our teaching and learning center while two of our staff members resigned and our budget was slashed. The provost, who was supposed to be working on permanently filling the director position, resigned. The unexpected departures of two full-time English faculty members over the summer meant that I taught two classes (one a new prep) and directed the center (in theory, a full-time job) as I completed the final course.

My world, yet again, shrank. I worked six days a week and did school work all day on Saturdays. I postponed car repairs and household chores. When I found a few minutes to peruse Facebook, I became jealous of those who could post seven days of black-and-white pictures that described their lives without words. The saying “darkest before the dawn” became my new reality.

Now at the end of my graduate school redux, I think it all worth the price. I found it hard to “just do the minimum” throughout my recent course work. Yes, I just needed to pass, but unlike many of my classmates (secondary English teachers who simply wanted or needed to teach dual enrollment courses at their high school), I had already thought much about the issues we studied. I had a great deal that I wanted and needed to say. My minimum effort resulted in five A+ grades in all five courses I took. Despite the pain of the situation, I loved the experience.

I grew to wish that my life had proceeded differently. Had I not been a first-generation college student who needed steady work and fell into a fairly typical path for women who came of age in the early 198os, I probably would have found my way into a PhD program the first time around. I would have loved being a scholar of writing and teaching writing. Instead, I have grown to love my small life, and my role as radical and revolutionary seeking to transform a community college writing program so that students there can have an educational experience equal to the Tier 1 research university right down the road.

I grew to wish that my life had proceeded differently. Had I not been a first-generation college student who needed steady work and fell into a fairly typical path for women who came of age in the early 198os, I probably would have found my way into a PhD program the first time around. I would have loved being a scholar of writing and teaching writing. Instead, I have grown to love my small life, and my role as radical and revolutionary seeking to transform a community college writing program so that students there can have an educational experience equal to the Tier 1 research university right down the road.

And I’m perfectly fine, completing my seven days of black-and-what photos all at once, in this blog post at the end of the best worst two years of my life.