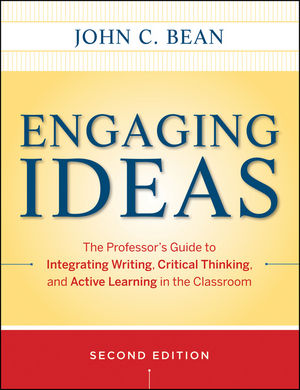

I again start this week’s post with full disclosure: I began my master’s degree at Montana State University in 1992. I served as a peer and professional tutor in the Writing Center. I was a grader and teaching assistant in both the first-year writing program and the Writing Across the Curriculum program. John C. Bean served as the writing program director and initiated the WAC program at Montana State; he left MSU a mere 6 years before I arrived. Therefore, I was trained to believe that John Bean pretty much walked on water–but I can’t say that hurt my education any.

In fact, as I reread Engaging Ideas to prepare for this week’s project, I realized how much  the idea of “writing as thinking” has influenced my teaching. I am committed to finding ways to allow my students to actually care about what they write, to helping them believe they have something to say, and to helping them say it to the best of their ability. I want to avoid what Bean calls “pointless essays that students do not want to write and that teachers do not want to read” (18). I also definitely agree with George Greenstein when he states, “…writing is thinking. In order to write about a subject, a student must think about it—and thinking is what we want our students to do. The clearer the thinking the better: the more often it takes place the better.”

the idea of “writing as thinking” has influenced my teaching. I am committed to finding ways to allow my students to actually care about what they write, to helping them believe they have something to say, and to helping them say it to the best of their ability. I want to avoid what Bean calls “pointless essays that students do not want to write and that teachers do not want to read” (18). I also definitely agree with George Greenstein when he states, “…writing is thinking. In order to write about a subject, a student must think about it—and thinking is what we want our students to do. The clearer the thinking the better: the more often it takes place the better.”

Lately though, I have been struggling to find ways to make that writing meaningful to my students again. That’s part of why I started my public writing assignment. In the current version of this assignment, I have my students write a series of short arguments online. Unfortunately, I already feel as if I need to find a better way to make my students think, to come up with ways to make them engage in the arguments they’re writing and not just go through the motions. After thinking about Bean’s recommendation that students be given “ill-structured” problems to solve (21), I began to look for better prompts for my students’ blog posts.

Coming down the stairs in my building on Tuesday, I stopped at my favorite mural: a satellite image of the United States at night. As I often do, I tried to discern which metropolitan areas are which, and then I wondered if my students could do the same.

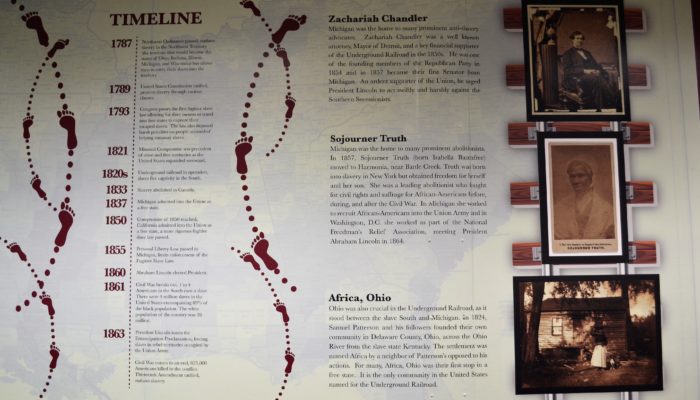

I also then began thinking about the example that Bean gives of the history professor who asks students to “present an argument that supports, rejects, or modifies the given thesis” (31). That’s when I knew that one of my new prompts is going to utilize my college’s “ambient learning” spaces.

My students and I are going to go on a short on-campus field trip. We’re going to talk about some of the murals, sculptures, and displays around the college. When we’re done, I’m going to give them a series of theses that are related to each of the stops we made:

- Light pollution robs humans of their sense of wonder about the universe.

- Abstract art is better than realistic art.

- Plastics are actually good because the amount of carbon they’ve sequestered has to help slow climate change.

- Identity politics has ruined our political process.

- Every college student should be required to take a geography course.

Since this is a hybrid/blended section of Composition II, their “online activities” for the week will consist of creating a short blog post that supports, rejects, or modifies one of those theses. The students will be asked to hyperlink to any external sources they use since they will need to search for evidence to support their view. The students must then also respond to some of their peers’ posts.

In this way, I think I’m hoping to enact the “knowledge transforming model of writing” that Klein and Rose investigated (434). For the first 10 weeks of the semester, I have taught my students the rhetorical moves they needed to craft an argument. Since, I think they have a functional understanding, I believe it’s time to put those skills to use in making bigger connections in the world.

As Klein and Rose point out, “The process begins with the writer pursuing a goal in the rhetorical space” (434). For my students, that rhetorical space is both their college-sponsored blog and the argumentation strategies we have discussed all semester. Within that space, I want students to combine old knowledge (what they may already know) with new knowledge (what they must go out and discover in order to answer the question) to create a new understanding about something they may have not considered before. As Klein and Rose describe it, “The writer works on this problem in the content space, retrieving knowledge from long-term memory, and deriving new inferences from it (or using other content problem solving operations, such as decision making). These inferences result in a transformation in the writer’s knowledge” (434).

Since my students must prepare for each face-to-face class meeting by completing a “Ticket in the Door,” I want to tie that task to their public writing assignment. I plan to ask two simple, reflective questions: “What did you learn about light pollution, climate change, plastics, abstract art, or geography by completing your blog post? How does that new knowledge change your view of the world?” This question was inspired by Dukewich and Vossen’s note that reflective writing in the social sciences and humanities “usually take on an especially introspective quality where students are asked to consider how they might interpret different concepts presented in a course, and how they see elements of those concepts represented in their own lives” (99).

I really view this public writing assignment as “writing to learn” and “writing as thinking.” Because I have them learning about topics that have little to do with writing, I hope I am also teaching them that writing is about learning and thinking, and I will need to explicitly explain this to my students. I will need to teach them this lesson instead of simply hoping they reach the conclusion by themselves. As my students progress into their other classes, I want them to understand that it’s not just about completing an essay; writing is about helping them to learn and to think.

Works Cited

Bean, John C. Engaging Ideas: The Professor’s Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom. New York: Wiley, 2011.

Dukewich, Kristie R. and Deborah P. Vossen. “Toward Accuracy, Depth and Insight: How Reflective Writing Assignments Can Be Used to Address Multiple Learning Objectives in Small and large Courses.” Collected Essays on Teaching and Learning, Vol. III. Windsor, Ontario: University of Windsor, 2015. ERIC. Web.

Greenstein, George. “Writing Is Thinking: Using Writing to Teach Science.” Astronomy Education Review 12.1 (2013): n. pag. ERIC. Web.

Klein, Perry D. and Mary A. Rose. “Teaching Argument and Explanation to Prepare Junior Students for Writing to Learn.” Reading Research Quarterly 45.4 (2010): 433-461.