Naming What I Know: My Threshold Concept of Literacy

Literacy is both an activity and a subject of study.

I know: I basically stole that line from Elizabeth Wardle and Linda Adler-Kassner (2015) in Naming What We Know. However, I have also just demonstrated three important characteristics about literacy:

- I decoded the writing in Naming What We Know and discerned the main point of the text. Additionally, I am encoding these very sentences that you are reading now. Therefore, I am able to use the technology called “writing” (Ong 1986) to encode and decode texts so that I can send and receive messages to someone not with me in the here and now. In other words, I am able to engage in the activity called “Literacy.”

- More than that, I am able to ask myself any number of questions about the stolen sentence: Is it plagiarism or remix? Maybe, it’s imitation? Does it need to be documented? If so, what is sufficient? Formal APA style? MLA style? A hyperlink? Wouldn’t it be fun to see how Addler-Kassner and Wardle answer these questions? And even more fun to understand why they give the answers that they give? In asking these questions, I am demonstrating that “Literacy” is a subject of study.

- Above all else, Literacy is learning. I was able to take what I read in Naming What We Know and apply it more broadly; that is learning. Literacy is how we pass on human knowledge. An oral culture is also literate; it can pass on learning to those immediately around them. However, literacy, that ability to use the technology called writing, allows us to build on the accumulated knowledge of our species at an ever-more rapid pace with those distant from us in time and space. Writing is our own learning made solid, and reading is making the learning of others our own.

Public Domain Image

Why Do These Characteristics Represent My Threshold Concept of Literacy?

- To me, those three ways of looking at literacy are transformative. I will never, ever look at reading and writing the same way I did in January when I started ENGL-W682. “Literacy Studies” is a discipline, a valid discourse community of its very own. Knowing how to read and write and understanding how people read and write (as well as learn to do so) are two completely different things.

- Writing as a technology and literacy as the activity of using that technology is particularly troublesome. Most of us like to think of Hamlet as “writing.” Instead, we need to be thinking about “writing” as if it were an axe or hammer—the most basic of human tools.

My Original Philosophy Has Changed Little

In reading through my philosophy from the semester’s start, I would change very little at this point. I consider this an affirmation rather than a failure to learn. I have made a few revisions, some refinements that are now essential to my understanding. For now though, I am content with this remaining a rather bad first draft, knowing that I will revisit and refine my thoughts in the near future.

Our first literacy is the spoken language we grew up with; it is how we can most easily make our learning available to others.

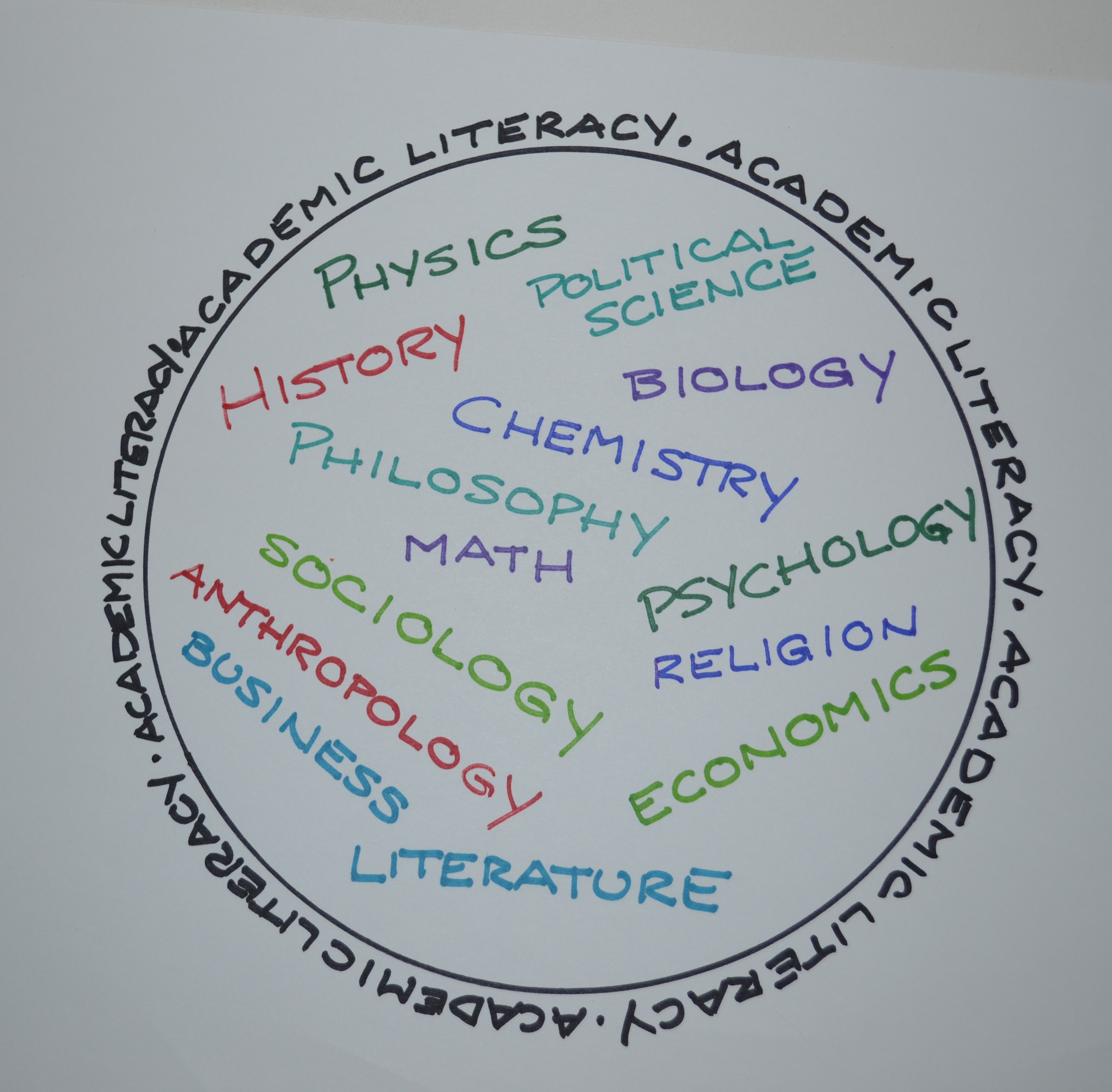

Basic reading and writing skills are simply an ability to use the technology we call writing. However, those reading and writing skills can be continually nurtured to develop the ability to read and write increasingly complex ideas. For example, when we have students take college composition courses, we are simply asking them to learn how to expand basic skills, to become literate in a different way—to read and write as a learner in order to contribute to the learning of others. Similarly, when students take introductory classes in their major, we are introducing them to the literacy values of that discipline; we then ask them to deepen their literacy in that discipline as they take ever-more advanced courses then begin their professional lives in that field. When we have students take general education courses, we are asking them to achieve some basic literacy in an area of learning not their own.

Literacy is a social activity, and it changes based on those around us. It is the context that matters when it comes to the correctness or appropriateness of that activity. As we go about our business and our lives, we—whether we realize it or not—move in and out of various discourse communities. The National Council of Teachers of English (2012) defines a discourse community as “a group of people, members of a community, who share a common interest and who use the same language, or discourse, as they talk and write about that interest.” A discourse community may simply be a group of people who enjoy a common hobby, such as skiing, or it may be a group of people who share the same professional interests, such as doctors seeking to find better ways to treat skiing injuries.

Throughout the course of our lives, we will be entering new discourse communities and consequently adopting new literacies. We will accept different jobs at different companies with different rules and language for communicating with each other. We will go through a similar process when we take up a new hobby or interest. Therefore, I think true literacy involves not only mastering some basic skills of spoken and written language common to everyone, but also the actual ability to move into a new discourse community and know how to learn the vocabulary and genres used in that community.

Perhaps it is the metacognitive ability to consider our own place within the various discourse communities that make up our world that best defines literacy. Shannon Carter (2008), Associate Professor of English at Texas A&M University-Commerce, calls for a pedagogy based on “rhetorical dexterity” that provides “a new understanding of the way literacy actually lives—a meta-cognitive ability to negotiate multiple literacies.” She argues for teaching students the value in understanding how they learned the literacies they already have and how that exercise will help them learn and feel comfortable in new literacies. Joyce Adams, Associate Professor in the College of Family, Home and Social Sciences at Brigham Young University, created a writing lab for social science students at BYU. Her research has led her to believe that students who believe they are not good writers often delay their advanced writing courses and/or complain about the amount of writing in non-English courses. Adams notes that since these students are “unaware of the amount of writing that takes place and the rhetorical differences that exist within different disciplines” it “hinders their attempt to enter their discipline’s discourse community.” As a result, she argues that teaching students successful metacognitive strategies can help them see the importance of writing tasks as well as increase their ability to effectively handle writing tasks in new situations.

Moreover, I now think that the contexts and forms of literacies are constantly expanding. In 1995, Deborah Brandt wrote, “The piling up and extending out of literacy and its technologies give a complex flavor even to elementary acts of reading and writing today. Contemporary literacy learners—across positions of age, gender, race, class, and language heritage—find themselves having to piece together reading and writing experiences from more and more spheres, creating new and hybrid forms of literacy where once there might have been fewer and more circumscribed forms.” For a long time, the printed page dominated what we considered literacy. However, we must now consider other media—such as television, film, computer programs, and everything on the internet—as a form of literacy. We can no longer limit “literacy” to the reading and writing on paper; we need to consider web spaces, blogs, SnapChat, Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook in the realm of literacy. Over 20 years, Brandt’s warning holds even more urgency for us today: “…problems with reading and writing are less about the lack of literacy in society than about the surplus of it. Being literate in the late twentieth century has to do with being able to negotiate that burgeoning surplus.” That problem has only multiplied in the twenty-first century. In a world where fake news passes for real and the violent broadcast their deeds for all to see, nurturing responsibility for our literacies has become an imperative. Note to self: I have lots to add from Keller and Brandt here.

Literacy is complex in many, many ways—and it is always a social, contextual activity. We cannot simply accept that literacy is the basic ability to read and write “standard English,” sitting in a room by oneself. Instead, we need to see literacy as fluid. It is the ability to take in as well as share ideas (both simple and complex) in person and across time and space. It is the ability to learn and employ new skills to communicate those ideas. Finally, literacy is the recognition that we can communicate and evaluate those ideas based on the social context, knowing that information we digest and share depends on those around us. And in a world where the internet allows us to narrow our discourse communities, shutting out or ignoring others, teaching the literacy of engagement and discernment will be our greatest struggle. Note to self: add lots of stuff from Naming What We Know, particularly the parts about entrenchment, cognition, and metacognition.

What Has Changed?

Me.

I no longer believe that “Writing and Literacy Studies” is a subfield of English. It is its own academic discipline. It’s literacy about literacy. Therefore, I absolutely can no longer teach students just the skill of writing. Instead, I need to teach them what writing is and what it does. Only then I can help them to learn to think about what writing is and what writing does every time they go to read and write something. Once they understand how the technology of writing works, then they can learn to ask questions about how they go about encoding and decoding texts. Finally, after we work our way through all of that, we can get to content, structure, style, and mechanics—the skill of writing.

References

Adams, J. (2014). Self-efficacy: a prerequisite to successfully entering the Academic discourse community. Teaching and learning 28(1), 17-35. Retrieved from http://go.galegroup.com.lcc.idm.oclc.org/

Addler-Kassner L. & Wardle E. (2015). Naming what we know: Threshold concepts of writing studies. Boulder, CO: Utah State University Press.

Brandt, D. (1995). Accumulating literacy: Writing and learning to write in the twentieth century.

Brandt, D. (2015). The rise of writing: Redifining Mass Literacy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Carter, S. (2008). The way literacy lives: Rhetorical dexterity and basic writing instruction. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Keller, D. (2014). Chasing literacy: Reading and writing in an age of acceleration. Boulder, CO: Utah State University Press.

National Council of Teacher of English (2012). Discourse communities. College Composition and Communication 64(1), 238. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.lcc.idm.oclc.org/

Threshold concepts: Undergraduate teaching, postgraduate training, professional development and school education. (2017). University College of London. Retrieved from: https://www.ee.ucl.ac.uk/~mflanaga/thresholds.html

Ong, W. J. (1986). Writing Is a technology that structures thought. The Written Word: Literacy in Transition. New York: Oxford University Press.